All of us who study anoles in the Caribbean share a PR problem: people think we’re partying on the beach all day long. Now, it’s true that that’s exactly what some of my colleagues do (you know who you are, but I’m not naming names), but there’s a problem with this approach: anoles don’t live on the beach! And for that reason, anole researchers generally do not either, at least not during working hours.

As we all know, anoles are characterized by the possession of two characteristics, an extensible throat fan and expanded subdigital toepads. But there are exceptions. The Cuban A. vermiculatus and A. bartschi (two of the finest anoles you’ll ever come across) have no dewlap whatsoever. And one species, A. onca, entirely lacks toepads, not even a hint of subdigital lamellae.

Where am I going with this, you might wonder? The answer is simple. Where do you think A. onca lives? On the beach! Anolis onca is the only beach-dwelling anole, or so it’s said. And for that reason, our South American Little Known Anole Tour (SALKAT) moved from the chilly Andes of Colombia to the smoking hot sealevel of Maracaibo, Venezuela to see what’s up with this species.

A few notes about Venezuela. Well, one mostly. It’s incredibly expensive. Who would pay $10 for a box of Froot Loops? Not even me. Or $9 for a can of Pringles? Ahem, well, it had been a good day. Rental cars cost more than $200/day, if you can find one (when we tried to get one at the Caracas Airport, the six rental car booths had, between them, two cars available). And hotel rooms are exorbitantly priced and also in scarce supply. We were told that the reason for that is that they were full of Cuban workers, sent over by the Castros to help their socialist brothers-in-arms. And, to be honest, the people we encountered–in the airport, at the hotel, etc.–often weren’t the friendliest.

A few notes about Venezuela. Well, one mostly. It’s incredibly expensive. Who would pay $10 for a box of Froot Loops? Not even me. Or $9 for a can of Pringles? Ahem, well, it had been a good day. Rental cars cost more than $200/day, if you can find one (when we tried to get one at the Caracas Airport, the six rental car booths had, between them, two cars available). And hotel rooms are exorbitantly priced and also in scarce supply. We were told that the reason for that is that they were full of Cuban workers, sent over by the Castros to help their socialist brothers-in-arms. And, to be honest, the people we encountered–in the airport, at the hotel, etc.–often weren’t the friendliest.

One thing was cheap, though, gasoline. They practically give it away. At one point, we only had 1/4 tank of gas, so stopped at a service station. I went in and bought a can of soda for $2.50, then paid the bill for the gas, which came to $0.60.

Any way, back to A. onca. Although this species is not well-known, a number of small papers have been written on its biology and natural history. The first was written back in 1971 when it was still considered to be in the genus Tropidodactylus (later sunk into Anolis by Ernest Williams); the author of the paper was then undergraduate James Collin, who went on to fame studying disease ecology in salamanders and heading the Bio Division at NSF. This and subsequent papers paint a somewhat contrasting view of where A. onca occurs and what it does; some report it on sand or at least on the ground, whereas others say it occurs in bushes.

Given that the species has no toepads and occurs at least sometimes on beaches, one’s natural tendency is to assume cause-and-effect: maybe toepads were evolutionarily lost when the species started occupying sandy habitats. Perhaps the lamellae get clogged with sand, or the microscopic setae are for some reason rendered impotent when in contact with sand grains. Many desert geckos are also padless, so it seems like a reasonable hypothesis.

With this in mind, our goal was to see what we could learn about habitat use and behavior of A. onca. Fortunately, Venezuelan herpetologists Tito Barros and Gilson Rivas, at La Universidad del Zulia in Maracaibo, who probably know more about onca than anyone else, kindly volunteered to show us their study sites and the lizards.

Our luxury beachside resort accommodations. The village of Playa Oriba was devastated by flooding a few years ago.

And so off we went to Playa Oribo, on the northwestern coast of Venezuela, about two hours and change east of Maracaibo. When we first got there, two things struck us: first, it was incredibly windy and, second, it was really hot. And a third thing: the lizards were really hard to find. Our inclination was to blame the weather for the saurian paucity; in my experience, hot and windy conditions are anathema to right-thinking lizards. However, our colleagues assured us that it was, in fact, always that windy (something that we’d been tipped off to by the literature), so that couldn’t be the explanation. More likely, they suggested, was the fact that not only was it the dry season, but it had been a very, very dry dry season, and so perhaps lizards were hunkered down.

Eventually, we did find lizards. To our surprise, they weren’t on the sand, or even on the ground. Rather, they were almost invariably in the branches of bushes. Given that many of these bushes were isolated, it’s probable that the lizards traveled overground to get from one to the next, but we certainly didn’t see it. Toward the end of our brief stay, Anthony Herrel found some deep in bushes in the shade. Perhaps that’s where all the lizards were. In any case, our study wasn’t very enlightening about why the lizard lost its pad. Maybe pad loss truly was related to the occupation of sandy habitats; perhaps the population we observed uses sandy habitats at other times of year, or in wetter seasons, or perhaps this is just a population that has expanded beyond its ancestral beach niche.

We did make two interesting discoveries, though. First, check out the corner of the mouth of this guy. I’m unaware of anything like this in an anole, although it has been reported in other lizards. In fact, in a paper published a few years ago, Kris Lappin and colleagues suggested that such coloration is an honest indicator of biting ability in collared lizards.

Second, when Anthony got the lizards to regurgitate their stomach contents, he found many of them packed with leaves, a most un-anole-like diet! Several papers have reported on the diet of onca, but no one has mentioned such folivorous fare before.

Clearly, there are many riddles yet to be explored in the mysterious case of the padless anole.

- New Article on Anolis roosevelti and the Question of Its Survival - March 16, 2024

- Lizard Diving Champions: Trading Heat For Safety Underwater - March 15, 2024

- Do Large Brown Anoles Get the Most Mating Opportunities? - January 6, 2024

Harry Greene

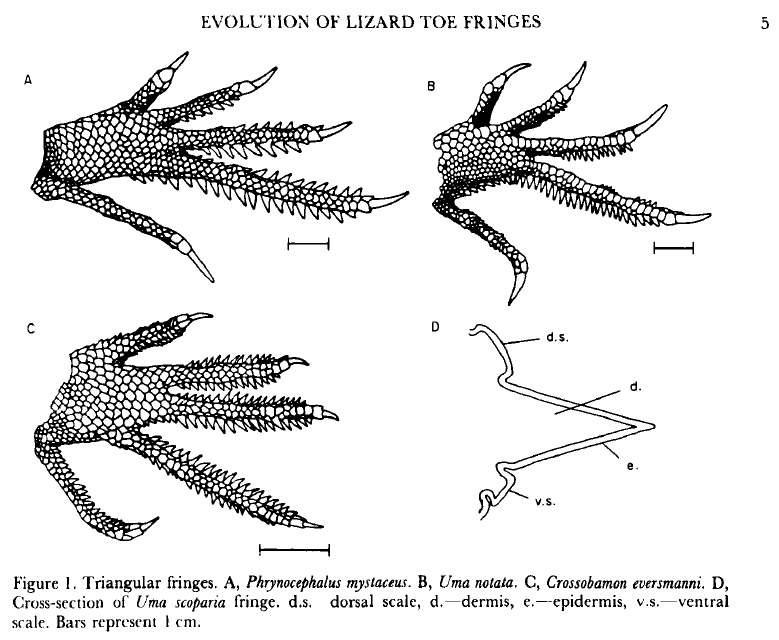

Looks to me like Anolis onca obeys Luke’s Law, formally formulated in 1986 (C. Luke. 1986. Convergent evolution of lizard toe fringes. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 27-16), by living on fine sand and having triangularly-fringed toes, as do Uma, Phrynocephalus, Teratoscincus, Scincus, and so forth–still another example of fascinating convergence among those fascinating anoles!

Martha Muñoz

Speaking of toe pads and Luke’s law – Anolis onca was the outlier species that distorted PC morphospace for his mainland species analysis and the reason was specifically their lack of toe pads. Maybe they also follow a Luke Mahler rule – one that isolates them in morphospace – because of their toe pads. Bad pun… sorry!

Martha Muñoz

I am referring to Pinto et al. (2008)

Harry Greene

The Law of Lukes [squared]?

Daniel Scantlebury

I believe I’ve seen that blue coloration in Anolis planiceps.

Miguel A. Landestoy

Neat Anole that A. onca! Read the name before but didn’t expected it to be padless… Pretty desertic habitat. It makes me wonder which habitats are not occupied by anoles in the neotropics!